Have you ever sat in a survey design meeting and felt like you are just going through the motions? We copy-paste old questions, tweak a few words, add a new section someone requested, and call it a day. Then, weeks later, we look at the data and realize… it doesn’t really tell us what we need to know.

I’ve seen this happen so many times. And, to be honest, I think the real issue is not the survey design itself – it’s the questions we ask (or don’t ask) in the first place.

We spend so much time collecting data that we sometimes forget to ask: Are we even asking the right things? And that got me thinking… some of the biggest breakthroughs in history happened not because someone found an answer – but because they changed the question.

Take Einstein, for example. He didn’t just ask “how things move” – he asked “what if time itself isn’t constant?” Florence Nightingale didn’t just ask “how to treat more patients” – she asked “why are they dying in hospitals in the first place?”

So what if we took that same mindset into humanitarian data? What if, instead of just designing surveys, we started questioning the questions themselves?

1. Albert Einstein: When Changing the Question Changes Everything

As someone with an engineering background, I’ve always admired Einstein – not just for his theories, but for how he approached problems. Most physicists at the time were focused on how objects move through space. Newton had given them equations, and they worked. But Einstein? He looked at the same problem and thought:

:.: What if time isn’t absolute?

.:. What if the speed of light is the only constant?

That tiny shift in perspective led to relativity theory, which changed physics forever.

The Humanitarian Data Parallel: Most surveys start with the same basic structure: What do people need? But what if we flipped the question?

:::.: Instead of “What’s missing?”, ask “What’s preventing access to what’s already there?”

:.::: Instead of “How many people need X?”, ask “What’s the real barrier to getting X to them?”

Suddenly, you’re not just measuring needs – you’re figuring out how to solve problems more effectively.

2. Florence Nightingale: When Data Visualization Saves Lives

Florence Nightingale wasn’t just a nurse – she was an information management powerhouse, a data pioneer who lived in the 1800s. During the Crimean War, hospitals were overwhelmed with injured soldiers. The obvious question was: How can we treat more patients? But Nightingale took a step back and asked:

:.: Why are so many soldiers dying in hospitals when they should be recovering?

She collected data, created a visual representation of what was actually killing soldiers, and showed that it wasn’t battle wounds – it was unsanitary hospital conditions. That one shift in questioning led to massive healthcare reforms that saved thousands of lives.

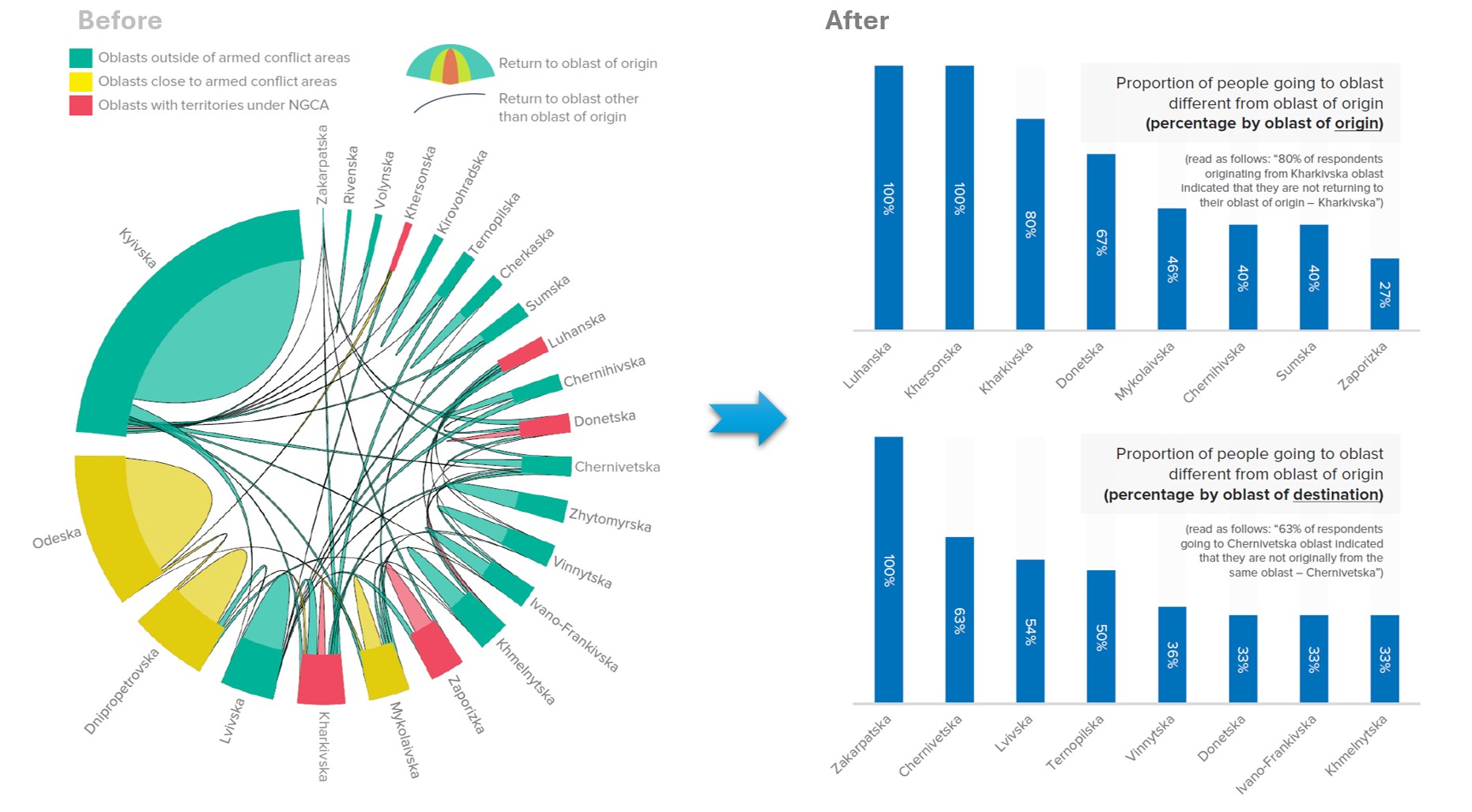

The Humanitarian Data Parallel: Think about humanitarian surveys today. We often focus on documenting suffering: How many people lack food? How many homes are destroyed? But what if we focused on prevention?

:::.: What patterns in past assessments could have predicted this situation?

:.::: What can we measure now that would help us prevent the next disastrous situation?

Data collection shouldn’t just be a reporting exercise. It should be a tool for proactive decision-making – just like Nightingale used it.

3. Amartya Sen: Rethinking Poverty and Well-Being

Amartya Sen, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, changed how we measure poverty and human development. For decades, poverty was seen mainly as a lack of income. Governments and agencies would ask: How much money do people earn?

But Sen questioned that question. He argued that income alone does not tell us if people are actually thriving. Instead, he asked:

:.: What freedoms do people have?

.:. Do they have access to education, healthcare, and opportunities?

His ideas led to the Human Development Index (HDI), which changed how the world measures well-being – not just in terms of money but in terms of capabilities and choices.

The Humanitarian Data Parallel: Most humanitarian surveys focus on measuring needs – food security, shelter, income. But what if we started asking about dignity, and long-term recovery?

:::.: Instead of asking “What do you lack?”, ask “What would help you rebuild?”

:.::: Instead of measuring vulnerability in isolation, assess what enables people to escape it.

Are we framing our questions in a way that captures the full human experience, or are we just gathering numbers?

Sen showed that how we define a problem determines how we solve it. Maybe it’s time we apply that thinking to humanitarian data, too.

Bringing This to Humanitarian Data: The Right Question Can Save Lives

It is not a secret that bad questions lead to bad data, and bad data leads to bad decisions. And sometimes, the biggest challenge isn’t collecting the data – it is having the courage to question the way we’ve always done things.

Albert Einstein once said: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about the solution.”

That’s because defining the right question is more than half the battle. If we ask the wrong thing, no amount of analysis will give us the right answers.

So before launching a new survey, let’s ask:

:::.: Does this question actually lead to action, or are we just collecting information for the sake of it?

:.::: Are response options structured so they’re clear and useful?

:.:.: Are we leaving room for unexpected answers, or forcing respondents into pre-defined choices?

::.:: Who benefits from this data? Who might be excluded by how we frame our questions?

And here’s something important to remember: Einstein, Nightingale, and Sen were not just asking better questions – they were challenging the status quo in ways that made people deeply uncomfortable.

Today, we see relativity, data-driven healthcare, and human-centered development as obvious. But at the time, these ideas were not just radical – they were disruptive, even offensive to the establishment.

:. Einstein’s ideas shattered centuries of Newtonian physics.

.: Nightingale’s data-driven approach was seen as unorthodox and faced resistance from military and medical leaders.

:: Sen’s human development theory pushed back against traditional economic models that focused solely on money.

They all faced enormous pressure because they refused to accept the “normal” way of doing things. They weren’t just scientists or reformers – they were disruptors.

So, when we challenge how we collect humanitarian data, when we question the way we frame assessments, we’re not just improving surveys. We’re making sure the data we rely on actually reflects reality – and leads to better decisions that change lives.

The biggest breakthroughs in history didn’t come from finding the right answer. They came from having the courage to ask a better question.

What if humanitarian data collection did the same?